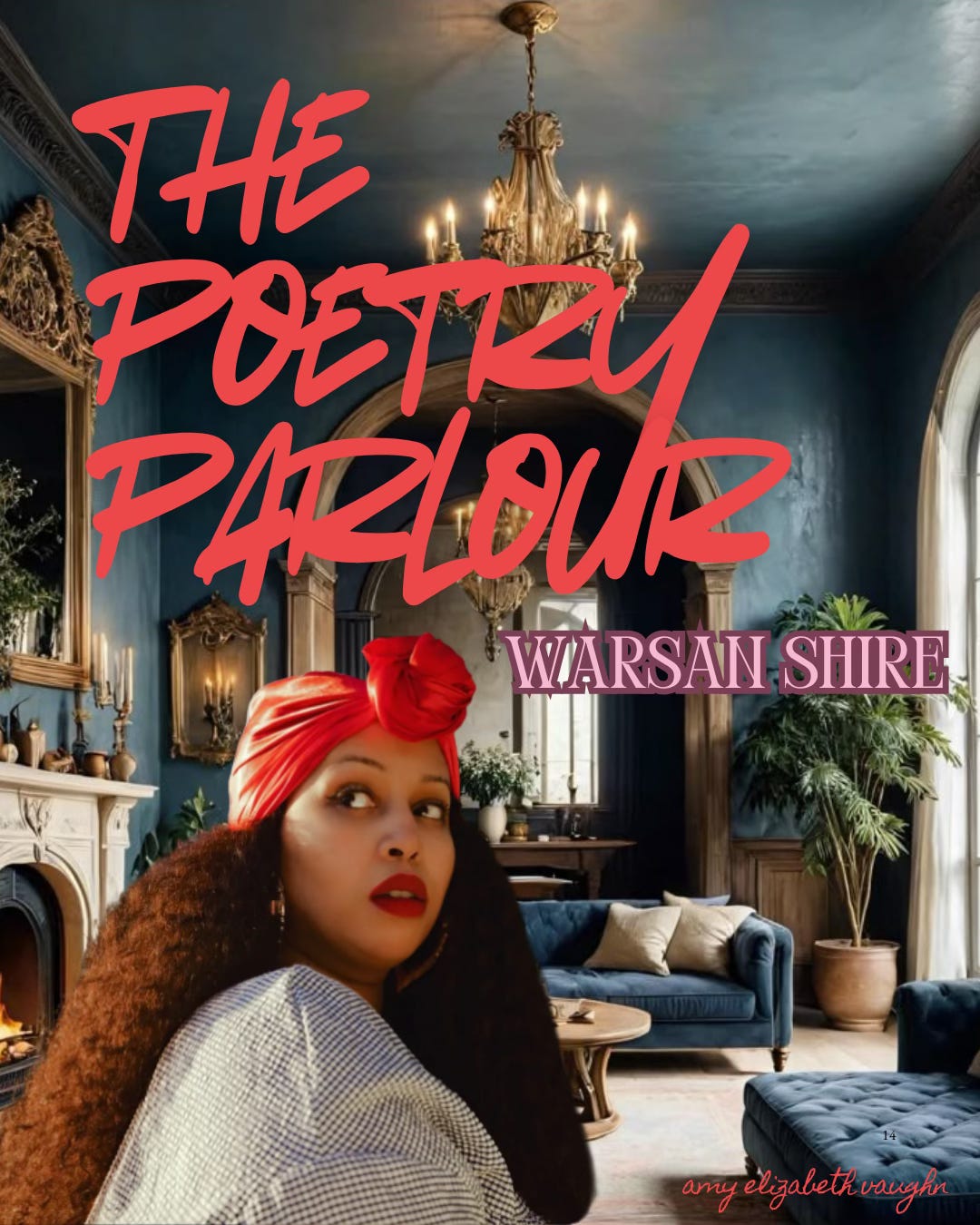

The Poetry Parlour: Warsan Shire

exploring raw & resonant words that bear witness to exile, womanhood & survival

Welcome to The Poetry Parlour, a space where poetry takes center stage. Here, we gather to celebrate the voices of poets—both rising and renowned—whose words move, inspire, and linger. Each post invites you into this intimate literary space, where verses are savored like fine tea, and the art of poetry is cherished in all its forms. Settle in, find a quiet moment, and enjoy the poetry waiting for you here.

Introducing the poet:

Born in Kenya to Somali parents and raised in London, Warsan Shire is a contemporary writer and poet whose work belongs on your bookshelf—if it isn’t there already. To date, Shire has published two chapbooks (Teaching My Mother How To Give Birth and Her Blue Body) and a full-length debut poetry collection, Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head.

Her achievements span both literary and multimedia projects, as highlighted in her Penguin Random House bio: “She was awarded the inaugural Brunel International African Poetry Prize and served as the first Young Poet Laureate of London. She is the youngest member of the Royal Society of Literature and is included in the Penguin Modern Poets series. Shire wrote the poetry for the Peabody Award–winning visual album Lemonade and the Disney film Black Is King in collaboration with Beyoncé Knowles-Carter. She also wrote the short film Brave Girl Rising, highlighting the voices and faces of Somali girls in Africa’s largest refugee camp.”

I personally first discovered Shire through her haunting poem The House, a piece that feels like walking through memories that aren’t mine but somehow live inside me. (*I’ve included Bless This House below, a slightly edited version of The House.) That led me to Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head, a collection that feels like sitting with a wise sister who has seen the world crack open and tells you exactly what that means, how it looks, how it feels. In her work, you will find poems breathing in themes of displacement, identity, race, womanhood, and survival; you’ll find tales of exodus and erasure, of mothers forced to leave their children behind, of bodies turned into battlegrounds. And you will listen.

As borders tighten and wars displace millions, Shire’s work feels prophetic. Commands attention. Her poetry doesn’t just bear witness—it refuses to let us look away.

Which poem speaks to you? How does Shire’s work make you feel? Let me know in the comments!

Introducing the poetry:

Souvenir

You brought the war with you

unknowingly, perhaps, on your skin

in hurried suitcases

in photographs

plumes of it in your hair

under your nails

maybe it was

in your blood.

You came sometimes with whole families,

sometimes with nothing, not even your shadow

landed on new soil as a thick accented apparition

stiff denim and desperate smile,

ready to fit in, work hard

forget the war

forget the blood.

The war sits in the corners of your living room

laughs with you at your TV shows

fills the gaps in all your conversations

sighs in the pauses of telephone calls

gives you excuses to leave situations,

meetings, people, countries, love;

the war lies between you and your partner in the bed

stands behind you at the bathroom sink

even the dentist jumped back from the wormhole

of your mouth. You suspect

it was probably the war he saw,

so much blood.

You know peace like someone who has survived

a long war,

take it one day at a time because everything

has the scent of a possible war;

you know how easily a war can start

one moment quiet, next blood.

War colors your voice, warms it even.

No inclination as to whether you were

the killer or the mourner.

No one asks. Perhaps you were both.

You haven't kissed anyone for a while now.

To you, everything tastes like blood.

From Our Men Do Not Belong to Us (Slapering Hol Press, 2014), published in association with the African Poetry Book Fund, Prairie Schooner, and the Poetry Foundation’s Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute, as part of the Poet in the World series.Chemistry

I wear my loneliness like a taffeta dress riding up my thigh,

and you cannot help but want me.

You think it's cruel

how I break your heart, to write a poem.

I think it's alchemy.

From Our Men Do Not Belong to Us (Slapering Hol Press, 2014), published in association with the African Poetry Book Fund, Prairie Schooner, and the Poetry Foundation’s Harriet Monroe Poetry Institute, as part of the Poet in the World series.Assimilation

We never unpacked, dreaming in the wrong language, carrying our mother's fears in our feet-- if he raises his voice we will flee if he looks bored we will pack our bags unable to excise the refugee from our hearts, unable to sleep through the night. The refugee's heart has six chambers. In the first is your mother's unpacked suitcase. In the second, your father cries into his hands. The third room is an immigration office, your severed legs in the fourth, in the fifth a uterus--yours? The sixth opens with the right papers. I can't get the refugee out of my body, I bolt my body whenever I get the chance. How many pills does it take to fall asleep? How many to meet the dead? The refugee's heart often grows an outer layer. An assimilation. It cocoons the organ. Those unable to grow the extra skin die within the first six months in a host country. From Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire (Penguin Random House, 2022).

Nail Technician as Palm Reader

The nail technician pushes my cuticles

back, turns my hand over,

stretches the skin on my palm

and says, I see your daughters

and their daughters.

That night, in a dream, the first girl emerges

from a slit in my stomach. The scar heals

into a tight smile. The person I love pulls

the stitches out with their fingernails, black sutures

curling on the side of the bath.

I wake as the second girl crawls

head first up my throat--

a flower, blossoming

out of the hole in my face.

From Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire (Penguin Random House, 2022).Bless This House

Mother says there are locked rooms inside all women. Sometimes, the men--they come with keys, and sometimes, the men--they come with hammers. Nin soo joog laga waayo, soo jiifso aa laga helaa, A man who won't listen to words, will listen to action. I said Stop, I said No and he heard nothing. Perhaps she has a plan, perhaps she takes him back to hers. Perhaps he wakes up hours later in a bathtub full of ice, dry mouth, flinching at his new, neat incision. I point to my body and say Oh, this old thing? No, I just slipped it on. Are you going to eat that? I say to my mother, pointing to my father on the dining room table, mouth stuffed with a red apple. The bigger my boy is, the more locked rooms I find. The more men queue at the door. Ahmed didn't push it all the way in, I still think about what he could have opened up inside of me. Ali hesitated at the door for three years. Johnny with the blue eyes came with a bag of tools he'd used on other women: one hairpin, a bottle of bleach, a switchblade and a jar of Vaseline. Yusuf called out God's name through the keyhole and no one answered. Some begged, some climbed up the side of my body like moss looking for a way in. Some said they were on their way and never came. Show us on the doll where you were touched, they said. I said I didn't look like a doll, I looked more like a house. They said Show us on the house. Like this: two fingers down the drain. Like this: a fist through the drywall. My first found a trapdoor in my armpit, he fell in, hasn't been seen since. Once in a while I feel a quickening, something small crawling up. I might let him out. Maybe he's met the others--males missing from cities or small towns and pleasant mothers, who tricked and forced their way in. Knock knock. Who's there? No one. At parties I point to my body and say Oh, this old thing? This is where men come to die. From Bless the Daughter Raised by a Voice in Her Head by Warsan Shire (Penguin Random House, 2022).

Until next time…

Thank you for reading and for being here. If you're enjoying my writing, I invite you to pull up a seat and subscribe to Once Upon a Writing. And if you’re able, your support as a paid subscriber would mean the world to me.

Follow my writing journey on my socials for more poems, editing services, updates & community interactions:

with love, amy elizabeth